By Nino Testa

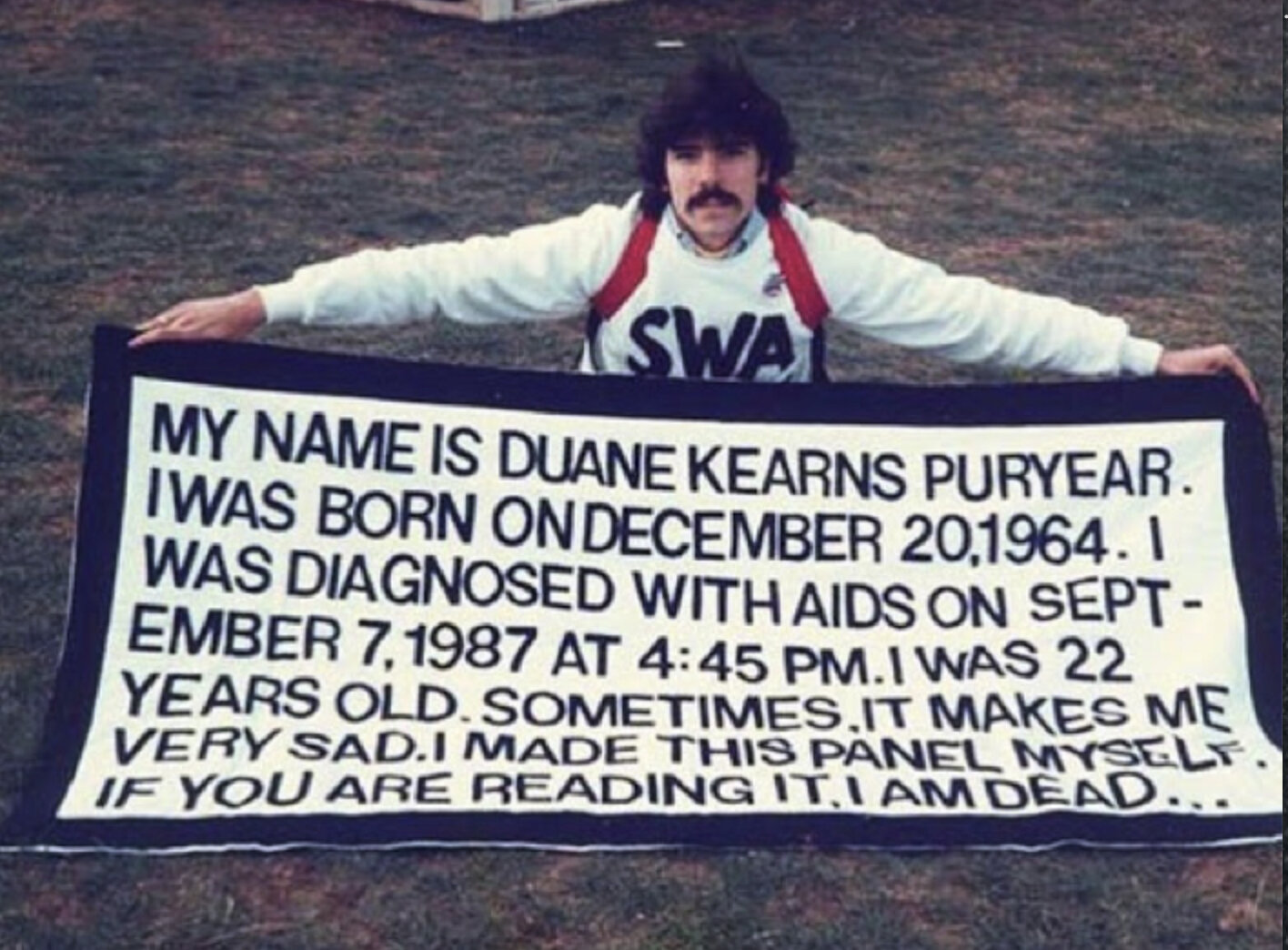

It is arguably one of the most memorable panels on the AIDS Memorial Quilt, made of white cloth with stark black letters that look like stenciling, but are actually individually cut and sewed fabric. It reads: “My name is Duane Kearns Puryear. I was born on December 20, 1964. I was diagnosed with AIDS on September 7, 1987 at 4:45 PM. Sometimes, it makes me very sad. I made this panel myself. If you are reading it, I am dead…”

It has become a symbol of the Quilt’s potential as a tool for advocacy, its image featured on AIDS Quilt promotional materials that insist “The Quilt will change your life.” In many ways, Duane Puryear’s story is like so many others represented on the Quilt. He struggled with anti-gay parents and developed his voice as an activist by organizing within the gay community in Dallas and participating in various direct action demonstrations for AIDS awareness and support.

Duane Puryear (right) with parents Doug & Martha

Unlike many other gay men of his generation, Duane reconciled with his parents, Martha and Doug Puryear, who eventually became his greatest supporters and the custodians of his legacy. His friends and family remember Duane as brilliant, charismatic, gregarious, handsome, dynamic, frank, and unflinching in his commitment to destigmatize HIV/AIDS. He dedicated his short life to art, education, advocacy, and prevention efforts. Duane was an aspiring artist, and his Quilt panel, this unique work of AIDS-activist art, became his most circulated design. But the famous panel also holds a hidden history. The truth is, despite the autobiographical statement it contains, Duane Puryear did not make the panel on block 2052 of the AIDS Quilt. While the origins of his panel are rooted in the AIDS activist movement of Dallas, the panel we see today has an unforgettable back story that demonstrates the Quilt’s dual function as both activist art and community memorial.

Duane Puryear was born in a snowstorm in Little Rock, on Dec. 20 1964. Six months later, his family moved to Baltimore, where Duane grew up, and then later to Dallas where he went to high school. According to his parents, Martha and Doug, their third of four children was immunocompromised from a very young age. Duane found his gender and sexuality being policed throughout his childhood, and he was the target of anti-gay violence and harassment in schools. Martha and Doug admit that they were ill-equipped to parent a child like Duane, although when Duane came out to them, Martha fully accepted and affirmed her son. It took Doug a little longer. Only after witnessing the care and love given to Duane, by the gay community he was part of in Dallas and St. Louis, did Doug come to challenge his own anti-gay sentiments. Later in their lives, Martha and Doug would both become active members of PFLAG (Parents, Family and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) and other LGBTQ community spaces, helping other parents learn how to meet the needs of their LGBTQ children.

Promotional materials produced by the NAMES Project, featuring Duane’s panel

Duane believed he contracted HIV after his first sexual experience while a teenager in Dallas. He later stated that his commitment to HIV education stemmed from his anger that he was not given accurate sexual health information as a teenager. After graduating from the Episcopal School of Dallas, he moved back to Baltimore to attend Towson University, but dropped out after his sophomore year and moved to St. Louis with a boyfriend where he took classes at Webster University and became an aspiring artist.

Duane used the black-and-white, textual aesthetic seen on his Quilt panel in many other works. According to his friends Dan Reich and Terry Carmody of St. Louis, his art was his political expression—and, like Duane himself, was direct, uncompromising, and in-your-face. His goal was to reduce the stigma and discrimination confronted by HIV+ people, which he had experienced firsthand. Reich recalled, for example, that when Duane converted to Judaism late in his life (after experiencing anti-gay discrimination in his Episcopal church), members of the observant community of his synagogue in St. Louis refused to let an HIV+ person be immersed in water in their mikveh. Undeterred, Duane completed the conversion ceremony in a hot tub at his rabbi’s home.

In a 1989 interview for an educational AIDS film, Duane recounted a horrific story of a staff member at a hospital in Dallas telling him and his mother that she wished that Duane “would hurry up and die” so that she wouldn’t have to clean his room. These kinds of experiences fueled Duane’s commitment to AIDS education and advocacy.

While living in St. Louis, Duane traveled back to Dallas to stay with his parents whenever he became sick. While he was in Dallas, Duane became active in the Dallas AIDS education and activist community. As a volunteer for the AIDS Resource Center he worked an AIDS hotline and helped found a speaker’s bureau that toured the city, including schools and hospitals, in the late 1980s, sharing personal experiences with HIV and disseminating safer sex curriculum. He won a recognition award from the ARC for this work in 1988. Duane was committed to destigmatizing people with AIDS and educating communities about HIV in the absence of organized and intentional education efforts by the City of Dallas or its public schools.

In a newsletter for the NAMES Project, Duane’s friend Jamie Schield paraphrases Duane: “Duane would say, ‘It’s not enough to sit and answer phones when they call. We have to go out there and speak. People need to see a face, a young face.’” Schield recalled how direct Duane was with teenagers, telling the story of his being gay and contracting HIV because the information that could have protected him was systematically withheld. According to Doug, Duane frequently did this work while quite sick, and sometimes sporting a t-shirt that read “That’s Mr. Fag to You,” an unthinkably provocative move in Dallas at the time, but typical of Duane’s irreverent and unapologetic attitude toward his life and his work.

In 1988, Duane supported the Dallas Gay Alliance’s efforts to sue the only public hospital in Dallas County, Parkland Memorial, for their discriminatory treatment of people with HIV, despite his father’s being employed as a psychiatrist there at the time. The DGA alleged a discriminatory practice of limiting the number of hospital beds dedicated to those who were HIV+ (a practice which Parkland denied). The lawsuit helped to catalyze broader activism around access to treatments, including AZT (which had long waitlists) and aerosolized pentamidine therapies.

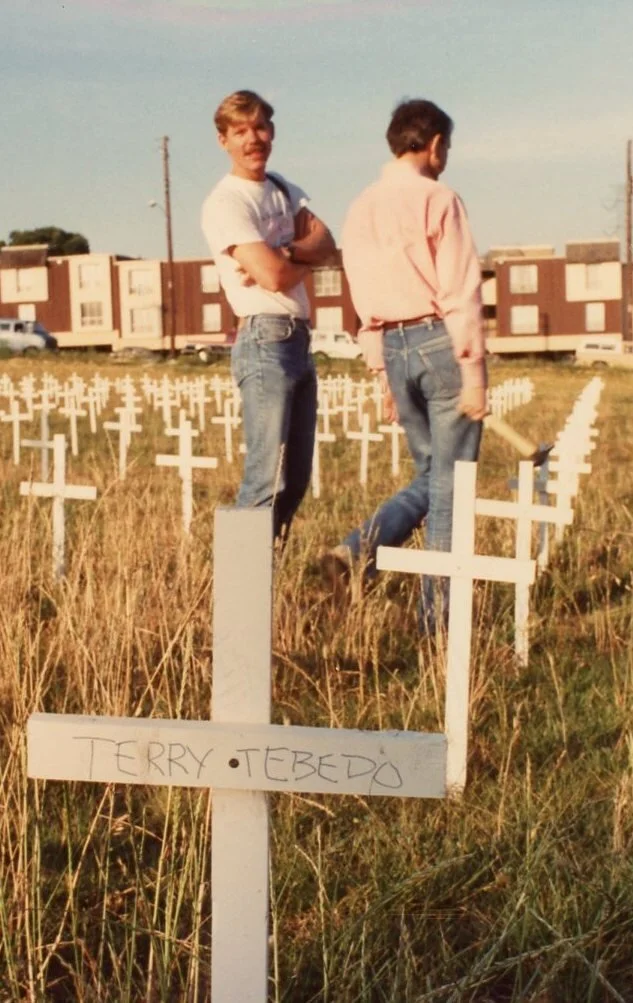

Potter’s Field demonstration

Duane was also active with the direct-action group GUTS (also called Gays with GUTS), which stood for both Gay Urban Truth Squad and Gay Urban Terrorist Squad at different moments. Through GUTS, Duane participated in historic direct-action demonstrations, including a guerilla Potter’s Field action in 1988. The city of Dallas had spent $500,000 to fill a hole at an abandoned construction site on Lemmon and Cole Avenues, while at the same time had spent only $55,000 on AIDS education and prevention. When the land was filled, GUTS activists, including Duane, constructed and planted over 700 white crosses with the names of local AIDS dead and staged a demonstration to point to the city’s budgetary neglect. The action resulted in an increase in AIDS funding to $552,000 the following year.

In May 1988, Duane volunteered at the Dallas stop of the first national tour of the AIDS Quilt. Duane’s parents said that Duane wanted to be the first person to make his own panel for the AIDS Quilt. Doug laughed at the memory of his son bucking the conventions of the Quilt: “Duane always had to do everything differently.”

Duane flew to Washington D.C. in October 1988 to be a part of the second national display of the Quilt, where he was proud to have marched with the Dallas contingent and read names as part of the ceremony.

Duane Puryear (on left) and a friend volunteering at the 1988 Quilt showing in Dallas

According to my interview with NAMES Project staff member Gert McMullin, the legendary “keeper of the Quilt,” Duane actually completed his Quilt panel on The Ellipse near the massive display that weekend in Washington, D.C. After the demonstration, Duane actually took the panel back with him to Dallas, intending to have it sent to the NAMES Project after his death. But when he left Love Field airport, he realized that he had accidentally left the panel on his Southwest Airlines flight.

Duane (on far right) marching with the Dallas contingent in the 1988 National AIDS Quilt march.

Frantically, Duane and his family attempted to recover the panel, but the airline was never able to locate the missing artwork, which was likely mistaken for trash and thrown away. Duane was distraught and disappointed. He had been especially proud of the ingenuity of his Quilt panel and believed that it would be an important piece of activist art, but he was also very sick. With his frequent travels between his home in St. Louis and his family’s home in Dallas, he was never able to remake the lost panel. He died in a hospital in St. Louis on October 8, 1991 (exactly three years after he completed his panel in D.C.). His parents, siblings, and friends, including Dan Reich, were by his side.

His parents were devastated, even though they understood his death was inevitable. They became part of an AIDS grief support group at White Rock Community Church, run by a legend of the HIV/AIDS community in Dallas, Marilyn Hollingsworth, who had lost her own son Rick to AIDS-related complications in 1987. Hollingsworth would eventually run the NAMES Project chapter in North Texas and used the Quilt to help many families and friends grieve their losses, in addition to raising funds for AIDS service organizations. According to Martha, about a year after Duane’s death, and after many visits to the AIDS grief group, Hollingsworth showed up at the Puryears’ door in East Dallas with a bag of supplies, including precut letters, and said, “You’ve got to remake this Quilt.”

At first the couple demurred and did not feel they could take on the emotional work of such a project. But eventually, they laid the fabric out on their dining room table and slowly, over the course of several months (with the help of Martha’s mother Gladys Kearns and Duane’s niece Katie, who was a toddler at the time), made an exact replica of Duane’s lost Quilt panel. Martha credits Marilyn, who died in 2004, with the recreation of Duane’s panel, which the Puryears would never have thought to make on their own.

The Puryears attended the grief group for over a year, and their relationship with Hollingsworth helped to resurrect and preserve this important piece of AIDS activist art. Martha and Doug’s feeling that they were a true part of the gay community—not just parents to a gay son—undoubtedly motivated their decision to recreate Duane’s panel.

Of course, no one who encounters block 2050 of the Quilt would know this history by looking at the panel, which is identical to the one Duane made in 1988. Duane’s panel, which was intended to be one-of-a-kind, a singular disruption of the familial mourning project of the Quilt and a powerful piece of political art, became, simultaneously, a memorial panel like so many others—made in grief by his family. Not only did the panel play an important part in their own grieving, but it helped Martha and Doug secure their son’s legacy and ensure that his art and activism would live on beyond his death. As Doug said: “He made his panel his way and made his point. And then we made the panel in the traditional way, which is for the healing of the families. And so we got both benefits of the panel both ways.”

Beyond the healing function of this memorialization, Martha believed in the political statement that her son had made, and wanted to be a part of its dissemination: “It was a way for Doug and me to say the same thing that Duane had said — that this is important.”

The panel’s history demonstrates how the Quilt was embedded in the broader AIDS activism of Dallas, specifically Duane’s own safe sex education, advocacy, and direct-action work. While the story of Duane’s panel may be exceptional, in many ways it demonstrates the dual nature of all panels, and the Quilt itself, at the intersection of grief and politics.

Duane Puryear holding his own Quilt panel in 1988

NOTE: For a more in-depth presentation of this story, go to:

Video article with Dr. Nino Testa:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tHLYf_D8NH4&t=363s

Footage of Duane being interviewed for the AIDS documentary Spread the Word:

https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1609571/?q=Duane%20Puryear

A Names Project publication about Duane:

https://texashistory.unt.edu/search/?q=Duane+Puryear&t=fulltext&sort=&fq=

Five audio interviews pertaining to Duane’s life, by Dr. Nino Testa:

https://digital.library.unt.edu/explore/collections/TESTA/

The Public Historian (University of California Press) academic article on AIDS activism and Duane’s life, by Dr. Nino Testa:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/156PAZfPOjk3fqSBgEzAt6tjkbwqdgY7R/view?usp=sharing